A new ransomware threat has emerged, targeting Linux systems and written in the Rust programming language.

Last week I spotted this post by @MalGamy12 about a new group that had created some ransomware. The group goes by the name Team Akita, with the ransomware dubbed AkitaCrypt. The post by @MalGamy12 is believed to be the first ‘In The Wild’ (ITW)’ sample available for analysis, uploaded to VirusTotal in early August.

Although this is the first time the ransomware has been publicly identified, the group responsible has been active since at least November last year. Evidence suggests they were offering access to the ransomware on a dark web forum. The screenshot suggests a fast cross platform solution with some of the following features:

- AES 256 or 512 with configurable salt

- Privilege escalation

- Undetectable and EDR bypass

- Smart or manual encryption

Sounds like a good sample to take a look at a bit further!

What Are We Working With

The sample can be found on VirusTotal here. There are other links available in the community comments to the likes of Triage and VXUG.

| File | Description | SHA256 |

|---|---|---|

| encrypt | ELF 64-bit | e648b3f73b75ca27ca5eb07dbcd1f00779bd49d81d3bf0c043dd8eb695fe4e95 |

Reviewing the Replay Monitor via the Triage links revealed that the ransomware did not process any files, instead producing multiple “directory not found” errors targeting Pelican and Nginx directories. This suggests a primary focus on web servers.

Technical Analysis

For this sample, I decided to start with some dynamic analysis, given there was some sandbox reports to baseline from. First off, some prep work (and unexpected runtime issues).

Setting Up

I initially planned to use my REMnux VM to analyse this sample, however, there was some challenges. After setting up the required directories*, I encountered an issue running the binary due to missing glibc libraries:

- GLIBC_2.32

- GLIBC_2.33

- GLIBC_2.34

*Note: if for example the pelican directory doesn’t exist the binary will still run*

I instead turned to my Kali VM which is where the analysis begins.

Dynamic Analysis

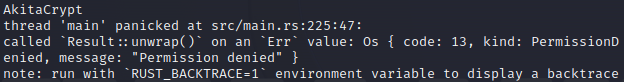

Despite adding the required directories, the first run as caused a panic and resulted in a “Permission denied” error.

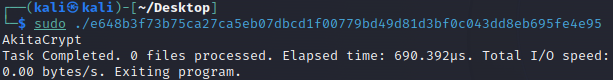

Ok, so let’s run as sudo and see what happens:

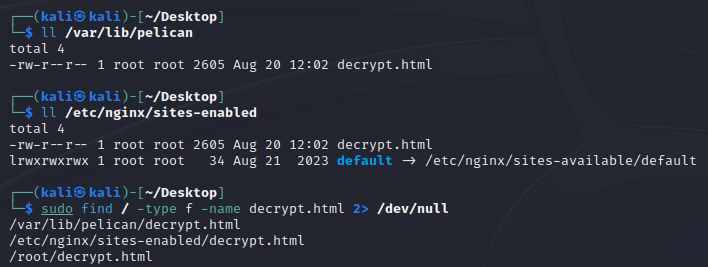

Bingo! Now, time to check the directories the sample required to run. For reference they are:

- /var/lib/pelican/

- /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/

Interesting… We have some dropped files called decrypt.html. A quick check of the file system finds one additional hit in /root:

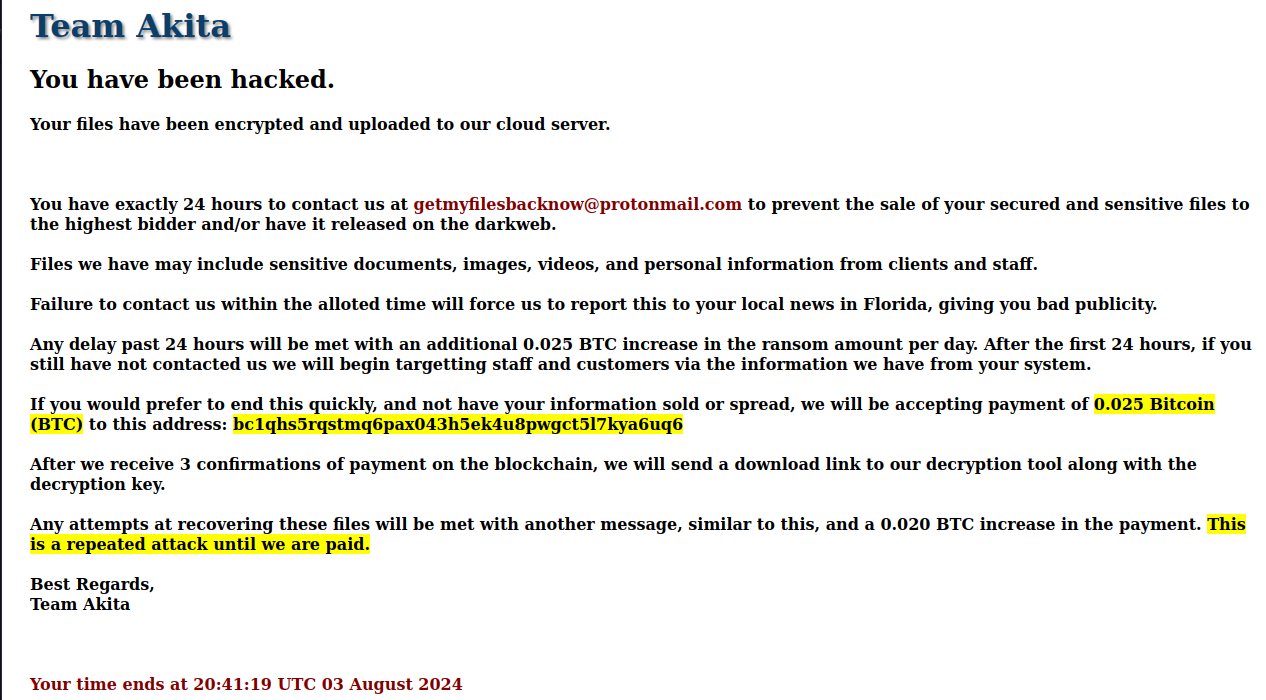

Taking a look at the rendered file we get the ransom note as seen below. Interestingly, the note seems to threaten reporting to local news in Florida if payment isn’t received. So was this targeted? The original VT submission was from Germany so maybe it missed the target? One item missing from the image below is the TA’s ransom note image, which is an Akita dog holding a padlock (image url in IoC section).

Static Analysis

Let’s take a look under the hood of the binary to try and understand a bit better what it is actually doing. For this, I’ll be using Ghidra. After letting the auto analysis do its thing, I checked for readable function names, which luckily this binary has. There is a namespace made by Ghidra during analysis that handily groups the primary functions of interest you would want in a ransomware program:

- encrypt

- decrypt_file

- encrypt_file

- main

- process_files

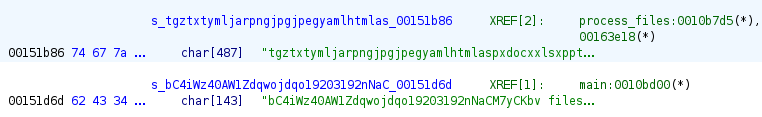

Before delving into the functions, a look at strings reveals some interesting items such as hardcoded paths (seen in dynamic analysis), the ransom note content, and a couple of large byte arrays that stand out (snippet below for reference). The top array looks like a concatenated string of file extensions, while the second one is a random alphanumeric string followed by the output printed to terminal by the program when executed as well as the usage details: Usage: ./encrypt [key]

To quote from this article:

It should also be worth noting that Rust strings are not null terminated. This can cause issues with reverse engineering tools during analysis expecting strings to end with a null byte. Since there is no null byte to denote the end of a string, strings can contain overlap depending on where the compiler lays them out in the binary.

At this point, the following assumptions can me made:

- Only targets specific directories

- Has a file extension list to target (asked Gemini to split the list - see IoC section)

- Hardcoded alphanumeric string was perhaps a key for encryption or decryption

Now let’s look into the functions to understand what is going on a bit more. This will be a mixture of code analysis and validation via gdb

main

The key actions of main can be outlined as such:

- Checks required directories exist

- Writes ransom note to the decrypt.html files

- Prints run/status messaging to terminal

- Call process_files (2 routes)

I wanted to understand why there was two routes to process_files so I started doing some hybrid analysis using gdb. In order to make this work, I had to get the image base from gdb, then reset the image base in Ghidra’s Memory Map window. To do this, first load the program in the debugger. Set break *main and run info proc mapping to obtain the start address. Then in Ghidra select Memory Map > Set Image Base and pop in the start address from debugger.

After setting breakpoints on both calls to process_files I ran two tests, one run as standard (no key) and another providing a key as an argument. This established a check for user input, which defines what is read and passed to the function. If a key is not provided, then a default hardcoded value is passed. The particular value (bC4iWz40AW1Zdqwojdqo19203192nNaCM7yCKbv) validates the theory from static analysis that it could be a hardcoded key.

process_files

This function primarily does as the name suggests:

- Validates the directories to encrypt

- Iterates for files and directories

- Checks file extensions

Flow from here depends on whether or not a key was provided as an argument. If no argument is passed, and the default key is used then the binary always calls encrypt_file. If a key is provided as an argument, then the flow defaults to decrypt_file. Hmm…

encrypt_file & decrypt_file

I’ve grouped these functions together because, well…they call the same function from_iter, which as we will see utilises a single algorithm.

First off, the encrypt/decrypt function will open and read data from the files. Next, the call to from_iter passes a memory address, and the data for encryption/decryption.

When diving into this binary, I anticipated a challenging exploration to uncover its encryption mechanisms. To my surprise, the encryption employed in this sample is quite straightforward: it uses a standard XOR operation with a provided or hardcoded key. In the binary’s code, the assembly instructions will look like:

xor bl, BYTE PTR [r12]

While XOR-based encryption is straightforward and easy to understand, it is often used as part of more complex encryption methods.

I was able to validate the above findings by utilising the debugger, and running the binary twice to recover my encrypted test files. Interestingly, there is no check in place to stop the ransom note from being encrypted as well!

As well as running the binary a second time, I further validated it was XOR by taking the hex bytes from an encrypted test file that contained the text: test text to encrypt, popping them into CyberChef and successfully decrypting back to plaintext.

Conclusion

Despite the claims made by the threat actors about the sophistication and undetectability of their product, a closer inspection reveals a much more basic reality — unless, of course, the binary was poorly configured with manual options that were supposedly available! The encryption method used is surprisingly straightforward, relying solely on a basic XOR algorithm. While XOR can be effective in certain scenarios, it is far from cutting-edge or advanced for a serious threat actor. This contrast highlights the gap between marketing hype and actual technical complexity. In reality, what we have seen so far is a relatively simple implementation, underscoring the importance of critically assessing the true capabilities of cybersecurity threats.

IoCs

Bitcoin Address:

bc1qhs5rqstmq6pax043h5ek4u8pwgct5l7kya6uq6

Threat Actor Email:

getmyfilesbacknow@protonmail[.]com

Ransom Note Image URL:

hxxps://i.ibb.co/NZvXnDP/akita.png

File Types Targeted:

- Archive formats: zip, rar, 7z, tar, bz2, deb, pkg, dmg

- Document formats: txt, doc, docx, xls, xlsx, pptx, pdf, rtf, csv, xml, ppt, ods, pages, key, numbers

- Image formats: png, jpg, jpeg, gif, bmp, ico, ps, tif, svg

- Audio formats: mp3, wav, ogg, aac, wma, aac, m4a, m4v, mov, flv

- Video formats: mp4, avi, mkv, wmv, mov, flv

- Executable formats: exe, bat, sh, py, class, js, asp, jsp, dll, bin, cmd, reg, ps1, app

- Database formats: sql, sqlite3, accdb, mdb, pst, db, dbf

- Other formats: html, asp, js, css, less, conf, ini, json, css, htm, xml, eml, tmp, part, xfrm, cfg, log, config, datastore, cache, acct, sql, php, bak, ttf, fonts, svg, fla, wmv, rar, 7z, tar, gz, bz2, deb, rpm, iso, img, cue, mdf, vcd, dvd, eml, msg, pst, ost, vcf, ic, storrent, wpc, download, rts, sub, ass, srt, nfo, sfv, vmd, dto, dsd, odp, pages, key, numbers, url, desktop, lnk, webloc, toast, cdd, pkg, app, run, vbs, cmd, reg, ps1, apk, ipa, zx, lzh, ace, rar, car, jb, C4, iW, z4, AW, mZ, dq, wo, jd, qo, 19, 20, 31, 92, nN, aC, M7, yC, kb

SHA256:

e648b3f73b75ca27ca5eb07dbcd1f00779bd49d81d3bf0c043dd8eb695fe4e95

Detections

Based on the IoCs from this sample, I’ve crafted a Yara rule to help detect this ransomware in the wild. If newer or updated samples are discovered then the rule can always be adapted from here.